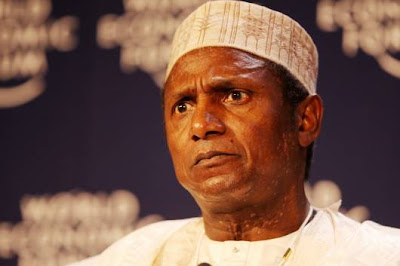

Last Friday, senior aides to Nigerian President Umaru Yar'Adua dropped a bombshell, announcing that he would be taking "a two-week leave of absence." Rumors that he suffers from a serious kidney ailment aren't new, and the news quickly reignited fears for the president's health.

Whenever rumors that a developing country head of state suffers from a life-threatening illness begin to swirl, political uncertainty (and political risk) rises. It's especially worrisome when the country in question is one of the world's ten largest oil producers.

But Nigeria adds an additional layer of risk-one that has everything to do with the country's tumultuous recent history and the religious fault-line that divides its northern and southern provinces. With the fall of dictatorship and the advent of democracy just a decade ago, governors in Nigeria's mainly Muslim northern provinces believed they had struck a deal with their southern Christian counterparts on a regional rotation of the country's presidency. For the next eight years, Olusegun Obasanjo, a southerner and a Christian, served as Nigeria's president.

But as the end of his second term approached in 2007, Obasanjo launched a bid to remove term limits from Nigeria's constitution and to extend the life of his presidency for (at least) another four years. Several northern governors angrily insisted that the time had come for a northern Muslim president. Southerners countered that northern autocrats had dominated the country for three decades before the election of Obasanjo-and that, therefore, the north's turn had not yet come. The country stood on the verge of a dangerous regional and religious confrontation.

Once Obasanjo accepted that he could not win the political fight and that the risk of open conflict had grown too high, he endorsed Umaru Yar'Adua, a northern governor and devout Muslim little known outside his native province, to succeed him. In April 2007, Yar'Adua was elected president. Despite charges of vote rigging, crisis was averted.

But it didn't take long for Yar'Adua's ill health to make headlines. In fact, it first came to national attention when he collapsed during a campaign speech and was flown to Germany for immediate medical attention. Yar'Adua managed to keep rumors about his health at bay long enough to win the election, but late last year he traveled to Saudi Arabia and stayed longer than originally announced. (Speculation centers on a deadly vascular auto-immune disease called Churg-Strauss syndrome.) Word today from his spokesman that the president will remain inside the country throughout his "vacation" and that his leave has "nothing to do with his health" will do little to ease growing doubts about his future.

Only Yar'Adua's doctors know the true state of his health, but the sudden announcement of his leave of absence will only further fuel doubts about his ability to cope with Nigeria's large (and growing) list of problems.

But here's the larger risk: Were he to die in office or to become incapacitated, Vice President Goodluck Jonathan, a southerner and Christian, would succeed him. Nigeria's northern Muslims won't quietly accept an abrupt transition to another southern presidency, and early elections would fuel tensions and the risk of large-scale civil unrest.

For those within the ruling Peoples Democratic Party who fear that Yar'Adua might take the party down with him, the search for a replacement will now pick up steam. Last week, former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, a northern Muslim whom Yar'Adua defeated to become president, publicly ended his bitter feud with former President Obasanjo-intensifying speculation that he means to run for president again two years from now.

Nigeria needs a president with a healthy supply of political capital. Efforts over the past several years to quell an insurgency in the Niger Delta region, home to nearly all of the country's oil production, have gone nowhere. Organized attacks on foreign oil workers and equipment -- and on Nigerian troops -- have shut in a significant percentage of Nigeria's production. Revenue from oil exports account for about two thirds of the government's budget, and neither brute force nor Yar'Adua's attempts at diplomacy have stopped the violence. The country faces severe electricity shortages. Inflation has surged past 14 percent, and the country's currency (the naira) has fluctuated wildly in recent days. Unemployment remains in double digits. Powerful labor unions threaten to strike unless the government substantially increases the minimum wage for public-sector workers.

All this in a country where the peaceful transfer of power from one elected leader to another is a relatively recent development -- a country that has proven an anchor for regional stability in recent years.

Though the extent of Umaru Yar'Adua's ailment remains secret, one thing is clear: Headline risk in Nigeria is not going away.

No comments:

Post a Comment